Ronnie Lee Loy

Ronnie’s story and obituary are below.

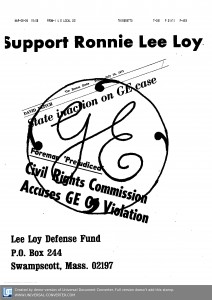

Ronnie Lee Loy – click here to see the pamphlet

(From a paper I wrote for MSW class 2/5/2003)

Ronnie Lee Loy

This past weekend, I called Ronnie Lee Loy, an 86-year-old friend of Chinese and Jamaican descent, to wish him a happy (Chinese) New Year. Ronnie now lives on Cape Cod, but 30 years ago, he was living in Lynn, Mass, and working in the General Electric Riverworks plant, also in Lynn.

In 1970, I went to work at the highest paid GE factory in the world in order to help the workers there make a revolution against capitalism and to establish socialism. GE in Everett, Massachusetts was an aircraft engine parts piecework plant. Customers included the US government, which needed jet engines to help wage the war in Vietnam. Workers there, mainly white and male, were openly patriotic with some openly racist and male chauvinist. They belonged to the International Union of Electrical Workers, IUE Local 201. Local 201 was the descendent one of the original GE unions with members in Everett, Lynn, and Wilmington Mass. I went there because I had become convinced that the industrial working class would be the agent of necessary radical social change in America and I had decided to go to where they were.

I was affiliated with a small, sectarian left wing political party that looked down upon the “old left”, the American Communist Party and various Trotskyite factions, as well as any other left wing organization that did not have perfect political understanding. The newspaper of this organization trumpeted militant headlines that included opposition to the war in Vietnam, exhortations to “SMASH RACISM” and timely news items like “WORKERS REBEL IN MINNESOTA”. I was not wholly aware of what racism was, but I had experienced some things that I knew would qualify when I had traveled through the South a few years earlier and had encountered separate “Whites Only” waiting rooms at the Greyhound bus terminals. I had, by the way, personally decided to integrate one of those waiting rooms by waiting in the “Coloreds” room, only to be asked to leave by its occupants who had probably concluded that I might not be the best horse to bet their safety on. My political wisdom by the time I reached GE was that the only way to defeat racism was by abolishing capitalism, a notion still debatable today.

I went to the plant and got myself hired as a “Move Man” by omitting my BA from my resume and playing up my furniture moving experience. My political party friends did not know that I was going to do this and did not seem altogether pleased. I later found out that they had several members working secretly in affiliated plants who had kept their politics hidden from everyone. Not knowing that that was the preferred strategy, and anxious to get the revolution moving, I went to the plant gates soon after I was hired to hand out leaflets and newspapers. This took about equal parts courage and stupidity. I knew that I was taking some risk, but only later, when I heard of the beatings of other activists in other industrial plants, did I realize the true risk potential.

What happened to me next seemed like serendipity, but was actually a gift that resulted from the militant history of the workforce. As the plant guards moved in to harass and intimidate me, an older worker appeared at my side, handed me $5., shook my hand, and turned and smiled at the guard’s camera. Other workers, even ones who supported the war, refusing to ostracize me, took what I was handing out, and supported my presence. Minutes before the shift change, I would stuff the literature into my pockets and go in to work. By the time I was laid off in Everett plant a few months later, I had started getting involved in local plant issues, like the harassment of a young woman by her foreman. I would produce leaflets exposing the injustice as well as the malfeasance of the union leadership. The layoff enabled me to “bump” into the Lynn GE Riverworks plant and found out that I had a reputation and that it had preceded me both in the shop and among management.

One day a stranger, a former union organizer who said that he had heard that I wanted to do something about racism approached me. He pointed out that three black workers had been fired in the past few months and that little had been done to defend them. One of those workers was Ronnie Lee Loy.

Ronnie had worked in Building 64 in the Medium Steam Turbine Division. He had been a rigger, someone who worked setting straps and chains to allow the cranes high overhead to lift and move the heavy rotors and other parts from workstation to workstation. He had a particularly racist foreman who would address him by shouting down the bay imprecations like “Hey, Chink (slur for person of Chinese descent) do this next”. Such behavior was not seen as unusual as evidenced by the fact that it went on for months and nobody but Ronnie even seemed to notice. It was also not unusual for a manager to have a plaque on their office wall saying, “I like colored people, everyone should own one”.

Ronnie needed his job and did not protest his mistreatment. Nonetheless, one day his foreman, in a rage, assaulted Ronnie in front of other members of management, and then fired him, accusing Ronnie of assault. With the help of the organizer we gathered together several shop stewards and other activists who agreed that it was time to do something about both the company’s racism as well as the union’s inaction. Before the struggle ended, three white shop stewards were fired and eventually rehired, hundreds of workers rallied to the stewards’ and Ronnie’s support, local activist attorneys agreed to help, charges were brought against GE through the Mass Commission against Discrimination and through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, prominent members of local management were called to testify and be humiliated when confronted with the tacit company policy, local union leaders were compelled to give support, and Ronnie won monetary damages and the offer of his job back.

The plaques came down off the walls. Members of management were sent to remedial class. And word was sent out to GE facilities across the land; blatant racism would no longer be tolerated.

(What I wrote for Ronnie’s memorial service)

(from Ronnie’s daughter) Ronald Lee Loy 92, of Marston Mills Ma, passed away on Saturday March 6th 2010, at his home in Cape Cod. He is survived by seven children, 17 grand kids, and 15 great grand kids. Ronnie worked for GE and then TRW until he retired. A memorial service was held on May 1st, 2010.

What a simple announcement for a man who changed the history of Local 201 and GE. On January 6, 1971, Ronnie, a kind and gentle man of Chinese and Jamaican heritage, was fired by a GE foreman after that foreman assaulted Ronnie in his office. In 1971 there was still open racism and discrimination practiced by GE management in the shop. For example, a foreman had a plaque on his wall that read “I like colored people, everyone should own one”. Minority workers were called by racial slurs and fired at a rate disproportional to their population, for minor offences. Before Ronnie, the racist practices were unchallenged.

After Ronnie was fired, some shop stewards got together, formed a group called Members against Discrimination (MAD), and distributed a flier about the fates of six minority workers, including Ronnie. The flier was headlined “GE: equal opportunity???” A few days later, GE fired Charlie Murray, a steward with over 16 years of service, for being “disloyal and defamatory”. On March 30, current Retirees Council head Kevin Mahar, seeking to support Ronnie and Charlie, went to his foreman to say that he too had handed out the leaflet. Kevin was fired followed by steward Richie Gallo.

With the help of volunteer lawyers, hearings were held before the Mass Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) which said that GE management was violating the Civil Rights Act by employing “someone known to be prejudiced …” Senior GE managers were forced to testify in public. A full page ad signed by university professors throughout New England ran in the Lynn Item. The case got significant publicity in the Boston Globe and other papers. MAD grew as more union members became active, leafleting at the plant gates, attending union meetings, working to get the stewards and Ronnie reinstated, and trying to get the then union leadership to be more responsive.

The case was won, the stewards reinstated with back pay, and a decent settlement was won for Ronnie. Ronnie never faltered in the pursuit of justice and, like Rosa Parks, a movement formed around him which changed GE shop practices nationwide, and led to a reformed Local 201. We also became good friends and I will miss him. – Frank Kashner, retiree, Local 201